A Minnesota PBS Initiative

A Minnesota PBS Initiative

A poster celebrating the dedication of the Minnesota Vietnam Veterans Memorial on Sept. 26, 1992 says this: “If part of you stayed in Vietnam, this is intended to make you whole.”

It didn’t. I hadn’t left part of me behind. I had come home with extra baggage that fueled 20 years of nightmares and flashbacks.

I was married and had a child when I got drafted shortly after graduating from the University of Minnesota in December of 1968. By August of 1969 I was a 23-year-old FNG assigned to Co. D (Stacked Deck), 2/12 Cav., Ist Air Cavalry Division, as a rifleman.

My very first day in the field we destroyed a hamlet out in the boonies beyond the old Phouc Long provincial capital of Song Be, about 65 miles north of what was then Saigon. We encountered no resistance yet we burned their huts, killed their livestock and contaminated their rice supplies.

As we moved on from that destruction I said to the guy ahead of me in the column, “Hey, I thought we were the good guys.” He responded succinctly: “F-n’ FNG.” It meant I didn’t know a damned thing about how things worked in the field. And he was right.

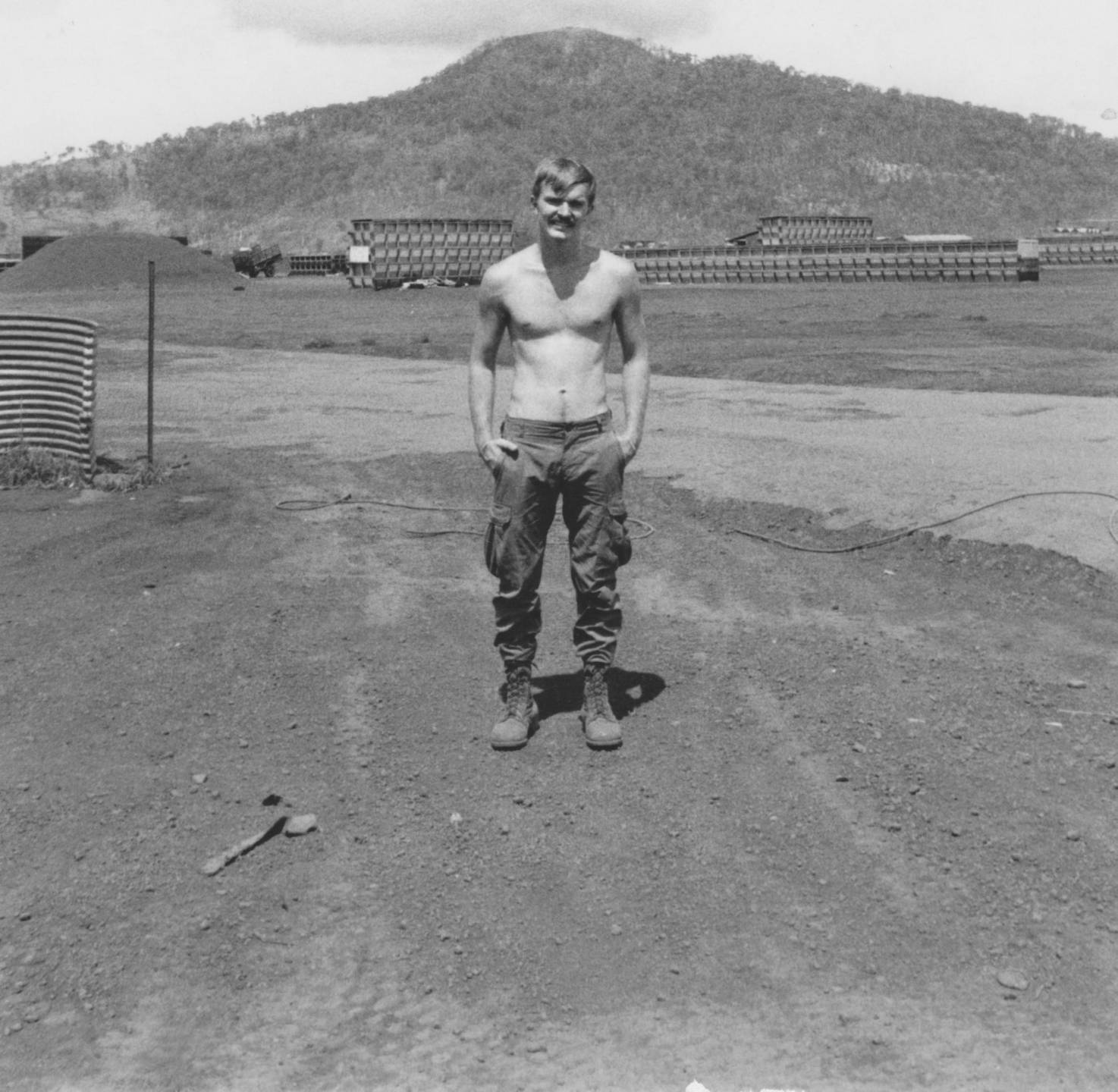

Me on Firebase Buttons near Song Be.

Weeks later I was the radioman in the point squad rushing to reach a hamlet where a long range recon patrol was pinned down. I was the first one to come under fire. I wasn’t wounded, but was briefly knocked unconscious. I don’t remember the rest of it. All I have are quick flashes: women and children scattering; huts burning and a bunch of Vietnamese boys (larger kids, teenagers maybe) charging at us before disappearing amid the clatter of an M-60 machine gun.

The thing is, I don’t even know if any of those little flashes represent reality. I don’t know why I don’t remember that firefight. It might be selective amnesia. Maybe, as a result of getting knocked out, my mind never recorded the event. Or maybe it was so awful that my subconscious won’t let me remember.

That firefight and one hellish night on a listening post, the enemy so near, methodically searching for us, seems to be what fueled my nightmares.

Add to that my own doubts about the morality of that war. It was less than a year after the My Lai Massacre of Mar. 16, 1968 that I got drafted.

Should I report and become part of that? But what about duty to country? My dad and many of his cousins fought in WWII. Could I turn my back on their efforts?

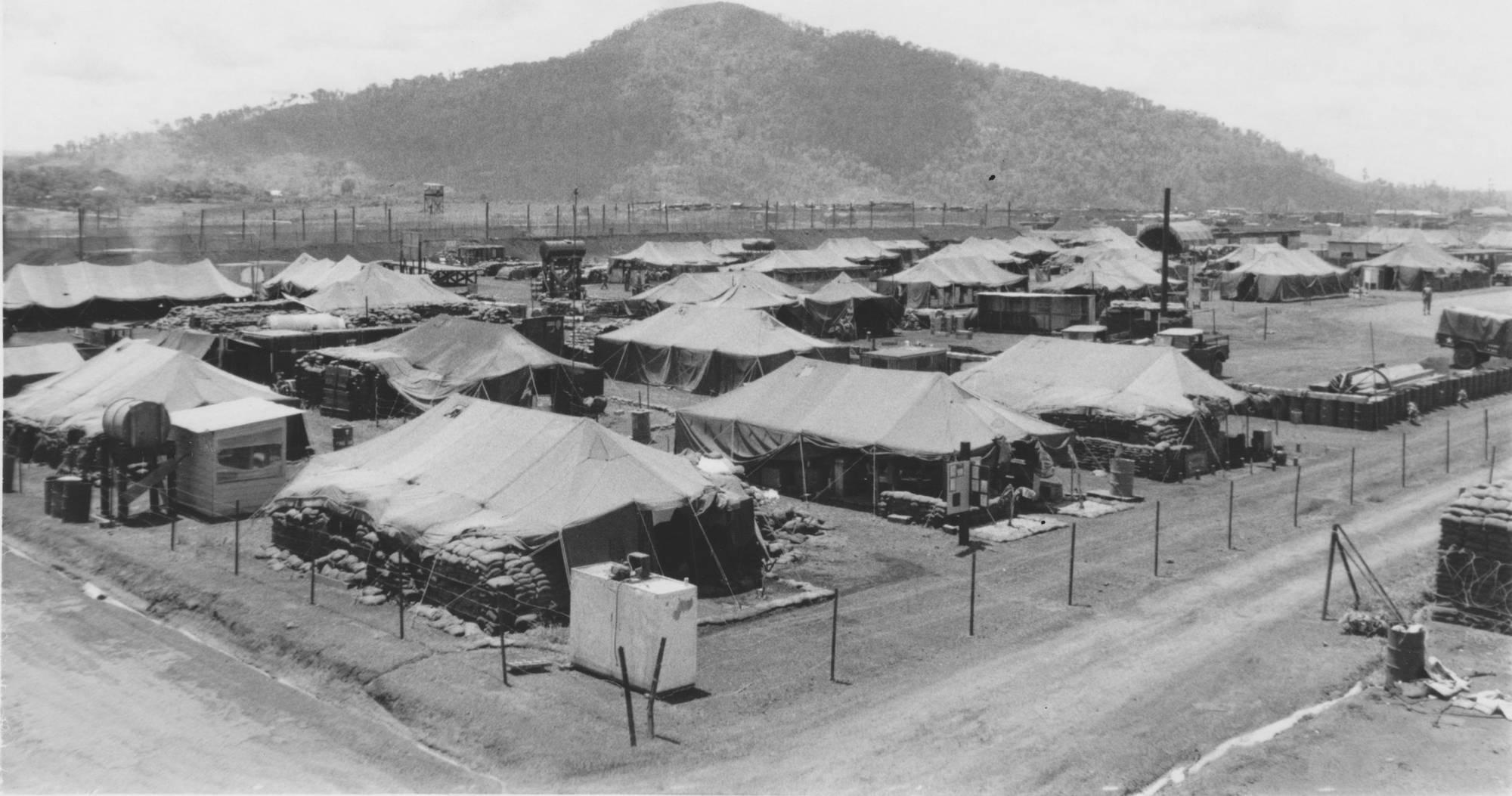

Add still more: In May of 1970, after I was out of the field and working as a clerk on Firebase Buttons, the Stars & Stripes carried a story about Ohio National Guardsmen killing four student protesters at Kent State University.

That only deepened my doubts about what I was fighting for.

And I wasn’t exactly welcomed home: Some jerk called me a baby killer as my family met me (I in my Class A’s) coming off the plane in Minneapolis. All of that created fertile ground for the formation of a poisonous Vietnam vet identity, one equally prone to bursts of violence or tears and depression. I just wanted to get my life back to normal.

Just pretend to be normal, and normal will catch up with you. So I did. I held a good full time job, bought a house, was active in church and played in softball and golf leagues. Twenty years of yearning for normal.

A vet friend who had been a Green Beret in Vietnam gave me this advice: Just pretend to be normal, and normal will catch up with you. So I did. I held a good full time job, bought a house, was active in church and played in softball and golf leagues. Twenty years of yearning for normal.

The turnaround began as I tried to cure myself of writers block. I had always enjoyed writing fiction as a kid, escaping to wonderful, imaginary worlds, but after Vietnam I couldn’t write that stuff anymore. One day I tried regurgitating a story a friend told me, adding nothing of my own, under the theory that doing so might lubricate creative processes. It was a children's story essentially, about a cat, and at the end some force caused my fingers to type something from the jungle.

Boom! Two years later I completed the rough draft to a novella I called Bamboo Dreams and when I typed “the end” the nightmares and flashbacks vanished. I’ve been reworking that therapeutic manuscript ever since. It is now called “No Escape” and was recently self-published in paperback. The cat features prominently.

Part of Firebase Buttons near Song Be, nui Ba Ra in the background.

This accidental therapy is why I’m telling this story. Writing about a traumatic event, retelling it over and over, can help loosen its hold. There’s an effort out there called “The Veterans Writing Project” and it has held free seminars for veterans all over the country. Its core curriculum uses the book Writing War: A Guide to Telling Your Own Story. A quote from their website says this: “Either you control the memory or the memory controls you.” I have not been part of that program, but enthusiastically agree.

Author Barbara Kingsolver, writing about the aftermath of September 11, 2001 but applicable to warrior veterans today, says this: “It is possible to move away from a vast, unbearable pain by delving into it deeper and deeper...You can look at all the parts of a terrible thing until you see that they’re assemblies of smaller parts, all of which you can name, and some of which you can heal or alter, and finally the terror that seemed unbearable becomes manageable.”

Story Themes: 1st Cavalry, Art, Coming Home, Creative Writing, Draft, Firefight, Kent State, Memoir, My Lai, My Lai Massacre, PTSD, Search and Destroy, Therapy, Veteran's Writing Project