A Minnesota PBS Initiative

A Minnesota PBS Initiative

Someone once told my dad the Vietnam Conflict was a waste of taxpayers’ money.

His eyes bore a hole through the man’s forehead, “It wasn’t a conflict, it was a fuckin’ war.”

The List

Although it was over twenty-five years ago, I remember we met on a soggy Saturday morning at the local Perkins. The waitress greeted us with the over-sized, glossy, plastic menus offering all day breakfast options and brought out our “never-ending” pot of barely tolerable coffee.

“Cream or sugar?” We both shook our heads “no,” thinking maybe a prayer would serve the coffee better. And without waiting for a response, packets of artificial sweetener, sugar and a small pitcher of cream were delivered by the waitress on a mission.

Our small chat began with family; my girls, Mom, Granny’s garden and how Grandpap crabbed and moaned because the red squirrels were in his attic again. Dad danced around the real point to the breakfast date and conversation. And, well, my father doesn’t dance.

My casual attitude took him back a little, but he hung in our conversation. I was going to visit history—he lived it.

“Hey, Dad, what’s on your mind?”

“Well, your Mom and I were chatting. She said she’s watching Amber and Whitney while you’re at your medical conference in D.C.”

“Yep.”

“Think you’ll have time for sightseeing at all?”

“Hmmm… haven’t exactly thought about it all yet, but I guess it’d be a shame not to hit the usual—oh, and Gallaudet, the university for the Deaf. My friend said she’d set up a tour for me. Remember my friend, Diane, the deaf professor? I took three years of sign language from her.”

He didn’t understand the history of Gallaudet, but smiled politely since I seemed excited. “Think you’ll go to the Wall?”

I added cream and sugar to my coffee; the prayer hadn’t helped.

“That’s the Vietnam War Memorial, right?”

He gazed into his coffee cup, his answer a muffled “yes.”

“Yah, I think I’ll probably go. It’s kinda sacrilegious not to when in D.C., right? I mean that’s like not going to the Lincoln Memorial or one of the Smithsonians. Haven’t been there before, I s’pose it’d be pretty interesting.”

My casual attitude took him back a little, but he hung in our conversation. I was going to visit history—he lived it.

An over-nourished waitress brought out our breakfast combo specials. Dad reached for the salt and the chit chat quieted as we concentrated on food.

A few bites into his meal, he awkwardly pushed his plate away. “Can I ask a favor?”

“Of course,” I said, still eating. Not even syrup coated the dry bites of pancake. Maybe I should have ordered the omelet after all.

The conversation started with a memory he had about how an old Vietnamese woman near their base camp washed all “the number one GI clothes” in the urinal with her feet (I loved his attempt at a Vietnamese accent, it sounded awful). This little old woman took pity on the young soldiers so far from home and cared for them. Dad said she stood about four feet but ran the camp laundry service as though she stood seven. He recalled her salt and pepper hair, mostly salt, and remembered a filter-less cigarette dangled from her lip, ashes always on the edge of falling, as she worked. For young men so far from home, she filled the role of a little old Grandma for many sent to fight. Dad gave her his canned peaches; she gave him clean tighty whities.

I saw the look on his face change as he recalled this memory; in all my twenty-four years, he’d rarely reflected on his years of tour. Although I’m the oldest child, my dad shared his experiences with my brothers more often than with me. Females in our family were protected, cherished, fragile little packages, sheltered if possible from the ugliness of the world.

He quickly moved on to the real reason he’d asked about my trip. He dug into his flannel shirt pocket and pulled out a neatly folded piece of paper. I took it from his hand and studied the list of twenty-some names. I strained to hear his hushed voice.

“These were buddies of mine…well, some of them I knew well ‘cuz we enlisted together and some were just there with me. On tour, you lose touch with what happens to people, unless of course you’re there when it happens. Do you think you could see if their names are on the Wall?”

“Course, Dad, not a problem.” I shoved the list into my purse, and it nestled between the expired coupons, tampons and the unwrapped gum stuck to the pennies at the bottom.

I chose to visit the Vietnam War Memorial on a quiet fall afternoon in October of 1991. At first, from a distance, the Wall appeared quite simple and unassuming; a long block of rock. Standing at the top it resembled a deep gouge into the landscape. Looking down, I noticed solemn visitors strolled the brick in-lay in front of the black granite laden with the engraved names of the fallen. Once facing the massive Wall, I discovered what first appeared to be simple and rather unassuming, was anything but. The colors of the fall leaves reflected off the sheen of the polished rock in the warm sunlight. A cool, brisk breeze swirled a few leaves at my feet.

The Wall arced in a subtle “V” allowing me to take in the magnitude of its length from one end to the other, the center of the “V” dug deeply into the earth with each end gradually diminishing in height as though healing the wounded hallowed ground. Etched letters filled each stone slab, top to bottom. Small American flags, teddy bears, and handwritten letters rested against the base along with bouquets of flowers.

Although insane traffic roared nearby, it seemed the wall sheltered those mourning from the chaos of the living. It was eerily quiet—yet strangely peaceful—protected.

Turning to my right, I noticed the massive height of the Washington Monument. I reached into my purse, feeling around for the list. A military guard standing duty informed me of the process necessary to locate a name. A large thick book, much like the size of the family Bible I received from Norway, rested on a pedestal. It contained the names of the casualties of this war; the size alone caught me off guard. From the first man that died in combat in 1956, to the very last on Vietnam soil in 1975, and every soul in between—the list of casualties seemed endless. The book identified the name, state and date of birth, when enlisted, and when and where the soldier died.

I thanked the guard, cracked my Diet Coke, and got down to my task at hand.

The first name on the list, while common, was nowhere to be found. The same went for GIs 2, 3, and 4. The fifth name on the list was identified as being on panel 46E, line 48. I ambled my way to the site and my eyes scanned the etched letters on the hard-black granite. My fingers traced the curve of each indented letter: R-I-C-H-A-R-D-W-A-Y-N-E-O-R-S-U-N-D. Granite panel 46E, line 48, had a name, and a family who mourned him, maybe even a wife and kids. And Dad knew him.

A gray-haired gentleman stood facing the black granite wall. He wore faded jeans and a black leather sleeveless vest with the American flag and eagle carrying the message “Never Forget.” One hand rested against the hard rock while the other held his hat over his heart. His head bowed slightly, his forehead touched the cold wall.

Feeling intrusive, I turned and studied the stone wall before me. A shadow appeared over the names, and I stood shoulder to shoulder with the veteran. “Need some help there young lady?”

“No, I’ll figure it out.”

I’d finally found a name. Oh shit, what was I supposed to do now? Dad and I hadn’t discussed the whole “what if” scenario. Unsure for the moment, I placed a small check mark by the name and continued my task of going down the remaining names on the list. There were a couple more misses, but the checkmarks quickly made the paper look like a failed quiz.

Was he there to say hello to an old friend? Or goodbye? I didn’t even bother asking if he needed help... Maybe he knew my dad… dammit, I should’ve thanked him for his service.

I folded the list of names again, this time carefully placing it in the zippered side pocket of my purse. I walked a short distance south of where I stood at the memorial with my downward gaze concentrating on each footstep. The rest of the afternoon I spent staring into the Reflecting Pool. Sitting cross-legged I turned to my right again; the Washington Monument stood tall, the Vietnam Memorial loomed in front of me. The still water captured my attention. The pool, deep and dark beckoned me to search its depth.

Mesmerized, I leaned forward, the images of the billowy clouds above me framed the image on the water’s surface. With all of this, I grew more and more embarrassed by the reflection glaring back at me. My self-absorbed immature response to the veteran tasted callous and insensitive.

Was he there to say hello to an old friend? Or goodbye? I didn’t even bother asking if he needed help. Maybe he knew Richard Wayne Orsund. Maybe he knew my dad. Maybe his name had been on Dad’s list sans a checkmark…dammit, I should’ve thanked him for his service.

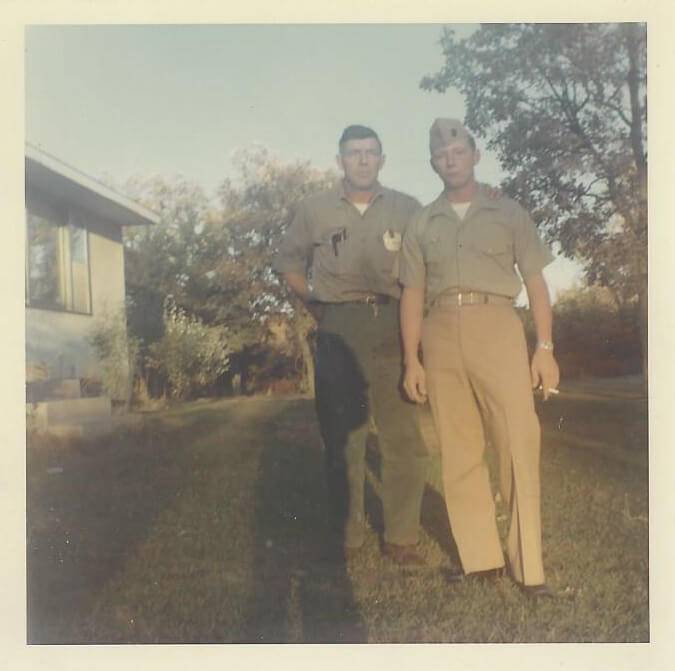

Although dad rarely spoke of his Vietnam tour, I knew he had been a scared eighteen-year-old in 1964, barely out of high school. He knew college wasn’t for him, so he enlisted before they could draft him. He thought enlisting was the honorable thing to do. I hadn’t understood the depth of his whole sacrifice. What did he know about war at eighteen?

Only a handful of pictures of him while stationed in Vietnam existed in a small shoebox I found hidden in his closet in my childhood home. I remembered how young and small he appeared standing next to a grove of banana palms—his light brown hair much thicker than the silvery-white with which I was most familiar.

Although I never knew him to smoke, I saw a pack of cigarettes rolled snug-tight in the sleeve of the white t-shirt hugging his torso and the bottoms of his Marine fatigues were tucked deeply into his boots.

The picture was faded, but I could make out a look on his face I wasn’t familiar with. A look of uncertainty. Perhaps uncertain he wanted his picture taken, uncertain of why he was there, uncertain of where he belonged, uncertain he would ever see the green and white stucco home he left again, uncertain why he stood next to a tree that bore a fruit he was allergic to—just uncertain.

Even though he rarely discussed his decision to enlist with us kids, he told me he remembered waking up on the floor once after he’d called his mother, my Granny Mike, a bitch. In his defense, Granny could peel wallpaper with a look when provoked.

In fact, when I was little I thought “don’t poke the bear” referred to Gran. Dad decided the Marine Corp life must be better than daily doses of Granny or college. I often compared Granny Mike to a drill sergeant in my mind after I heard his story.

Staring into the deep water of the Reflecting Pool, I began to think of questions I never asked Dad.

Did he really know what Vietnam was about? Did any of the buddies he swore to protect understand? Maybe he thought he would come home a war hero, like his father from World War II, and have his name etched onto a plaque in the center of City Square in town.

Perhaps he imagined the American flag flying high above those gathered in honor of his willingness to put his own life on the line to defend and protect the little kiddoes playing in the park or the teenagers flirting in backseats at the 65 Hi Drive-In. Growing up, Dad, his little brother, and parents would pay homage to the fallen and celebrate the living veterans circled around that flagpole and plaque every Memorial Day. My dad, a proud Marine, grew up with big Army boots to fill.

Dad was famous for comments such as “whether you think you can, or you think you can’t, either way, you’re right.” And God forbid you get hurt, because his post-injury response was “well, you know where you can find sympathy; right between shit and syphilis in the dictionary” (my mother hated that one). And of course, the one I heard most often, especially as a teenager, “excuses are like assholes; everyone has one and they stink.”

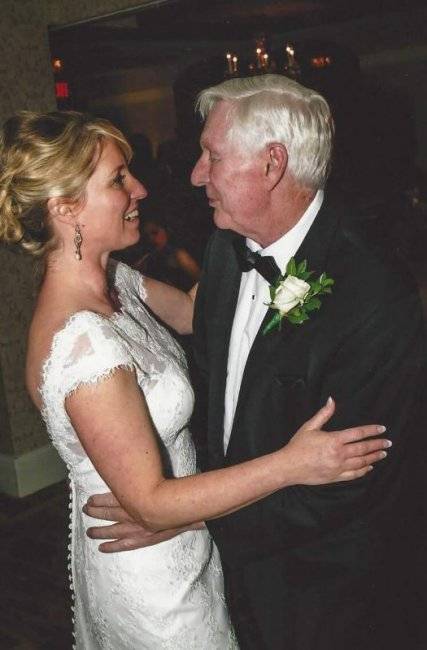

My dad was a wonderful, loving, practical, and hard-working Marine of a father. Toughened by whatever helped him survive Vietnam, he was able to come home and not have his name etched in the black granite. Somehow, the callousness war created softened, and he learned to love again despite life’s ugliest influences. And I loved him more for it now than ever before.

Gazing back at the veteran concentrating on the Memorial I began to think. Dad wasn’t what I, or perhaps anyone else, considered the Hollywood version of a Vietnam Vet. He rarely drank, didn’t smoke, sported short hair, held down a job, and raised a family. Hell, the only leather Dad owned was a pair of well-worn work gloves.

Sometimes, he mumbled at the protestors or anti-government rioters on TV during the news… “Pick up a gun and march the border asshole…” My brothers and I knew something occasionally made Dad angry, but we never discussed it—ever. I guess instinctively—even as kids—we knew not to ask questions; something told me the answers weren’t easy to understand anyway.

Dad didn’t like fireworks, but I never knew why; so, my mom and aunts dutifully dragged station wagons full of kids, blankets, and lawn chairs to the park on the Fourth of July. All my uncles stayed home—turns out they didn’t care much for the fireworks either.

I arrived back into Minnesota. Ashamed, it took me over a week to gather the nerve to face my dad again.

I often found myself picking up the phone and dialing my parents’ number, only to hang up just after the first ring.

What would I say? “Gee, Dad, sorry I was such an immature and inconsiderate jerk that I didn’t understand what the list of names could have possibly meant to you until I touched the names of your dead buddies etched in stone…” seemed the most appropriate opener.

But instead, I picked up the phone and managed in my best casual voice, “Hey Dad, wanna grab a crappy omelet? This one’s my treat.”

“I’d love it.”

Dad and Grandpa.

War does not discriminate who it kills… or why. And now, twenty-six years after being honorably discharged a veteran, he had an answer to a question that plagued him.

This time there wasn’t any small talk as we both swirled our hideous coffee. Eventually I broke the silence by asking if he would like his list back.

His steel-grey eyes fixed on mine. He nodded. I took it from the zippered pocket of my purse and slid it across the sticky, syrupy table top. His hand brushed mine as the precious information exchanged hands. He slid the folded piece of paper into his shirt pocket.

There were no words.

Just a very solemn nod of his head said he knew his hopes had been dashed—there was a reason to give the list back. I found at least one name. He feared this, although I hadn’t understood the depth of emotion until it was written on his face. Years prior, Dad placed his life in the hands of another Marine and asked that person to do the same.

Some men returned. Some did not. There was no rhyme or reason to it, just a fact of life. Dad returned. War does not discriminate who it kills… or why. And now, twenty-six years after being honorably discharged a veteran, he had an answer to a question that plagued him.

We never spoke of the list again. But I now had a very different appreciation of my Dad, the son and brother, uncle, husband, and the Vietnam Veteran.

He entered the war an innocent and frightened eighteen-year old. He came home a man. A dependable man who loved and cared for his family in ways I didn’t understand until I became a parent myself.

He entered the war an innocent and frightened eighteen-year old. He came home a man. A dependable man who loved and cared for his family in ways I didn’t understand until I became a parent myself.

Growing up on the farm, I saw him work from the first crack of dawn to the light of the moon. Even then, in the pitch-black dark of night, I occasionally heard him get up to help a struggling heifer birth a calf. “Can’t let the profit die” he’d say half-awake over a morning cup of coffee.

On more than one occasion, he drove thirty minutes one way in the middle of the night to pick me up from a sleepover I just had to go to, even though he knew I’d get homesick before bedtime. He danced with my mother in the kitchen, spanked naughty bottoms, and built blanket forts on rainy days. Dad fixed my chronic earaches with his “special medicine,” so I’d sleep like a rock through the bulk of the pain. As a little girl, I thought he was the perfect example of dedication and devotion—as an adult I knew it as fact.

Through all my years in medicine, I would meet male patients my father’s age and gently inquire as to whether they were Vets. Almost instantly, a profound sadness would veil their faces and heaviness would enter the room. Something about coming home weighed on the shoulders of every survivor, something that hardened the heart and thickened the skin. I prayed for all the men who did not receive a check mark, the ones like my dad.

It’s been twenty-five years since my first visit out of many to the Vietnam War Memorial, “The Wall.” Each time I visit I think of Dad’s list. To this day, I don’t know where that piece of paper is but I still remember each of the check marks. Oh sure, the names have escaped me, but their selfless sacrifice and willingness to serve our country hasn’t. I pray they did not suffer, but in my mind, I know better.

Me and dad.

About the Author

Cami attends graduate school at Hamline University in the MFA-Creative Writing program. As an undergrad, she received the O'Leary McCarthy Scholarship for Excellence in Writing, English Honors, and was an honorary member of the Delta Phi Lambda Writing Society. She and her husband are part-time empty-nesters living in scenic Stillwater. "The List" was written out of the deep respect and admiration she has for her dad, the man who raised the bar for every other man in her life.

Story Themes: Art, Cami Stenquist, Children of Veterans, Creative Writing, Enlisting, Family, PTSD, Read, Reflection, Relationships, Stillwater, The Vietnam Memorial, The Vietnam Wall