A Minnesota PBS Initiative

A Minnesota PBS Initiative

The Mekong River begins as a trickle in the mountains of Tibet. Twenty-six-hundred miles downstream, the river is gorged in porridge-brown water, spreading into four fingers of the Mekong Delta. They’re called My Tho, Ham Luong, Co Chin and Bassac, and each one empties their discarded offal of humanity into the sea.

It’s December. The ocean has turned mean, angry and unforgiving of poor seamanship. Our fifty-foot Swift Boat was not designed for these seas. This patrol will be on the smooth Ham Luong River—but it will take three hours to get there through tormenting seas.

I must be crazy, but I’d rather risk the possibility of being shot at in a river than the certainty of a brutal beating at sea. Our transit to the Ham Luong is cruel.

Blue-gray clouds merge into the sea as if there’s no horizon. We run into a stinging squall with wind gusting like hammers, walls of green water marbled with white foam slamming our pilothouse. Gnau is driving and I stand ready to relieve him if needed and ready to puke if not. I could use a triple dose of Dramamine. The crew is gripping handholds as we’re launched into the air by an ugly curling whitecap.

We enter the mouth of the Ham Luong and we’re lifted and accelerated by a massive wave like we’re a surfboard caught by a tsunami. As we enter the smooth, almost tranquil Ham Luong Taylor uncovers the twin-fifties up in the gun turret. Taylor has the watch, squatting on top of the pilothouse, scanning the river with binoculars.

A Vietnamese sailor tosses a line and we tie alongside. An old man appears to be the captain. Toi asks for identification papers while Taylor and Moison leap aboard to begin a search.

“Skipper,” Taylor calls out, “there’s a large junk comin’ upriver.” “Okay, standby for board and search,” I say to the crew.

It’s not an enthusiastic command, but one of routine. I don’t feel we’re accomplishing anything, searching junks and sampans. Out of three-hundred searches, we’ve found only two suspected Viet Cong, one with too much money, and the other with a large stash of medical supplies.

As we close on the junk, Toi calls out over our loud speakers, “Lai dai, lai dai,” Come here, come here.

Toi is our Vietnamese Navy liaison. He’s barely five feet tall and thin. He has a nice smile and his uniform is spotless, a reflection of pride he must feel for his navy. The old junk is easily ten feet longer than our Swift Boat, over sixty-feet, bigger than any vessel we’ve searched. Her brown weathered sails are furled and she’s slowly making way with the putt-putt sound of a small diesel.

A Vietnamese sailor tosses a line and we tie alongside. An old man appears to be the captain. Toi asks for identification papers while Taylor and Moison leap aboard to begin a search.

This young South Vietnamese girl epitomizes the image I have of the girl in my story. It was taken by Senior Combat Photographer Arthur Hill, USN.

I stand near the aft helm, watching the old man. He’s barefoot, wearing baggy black shorts that cover his knees and a filthy shirt three sizes too big. Hoffman is crouched on our cabin top, Gnau on the fantail and Suggs on the bow, each with an M-16, the safety off, keeping an eye on the crew of the junk.

To protect Taylor and Moison, they won’t hesitate to shoot. “Skipper,” Taylor yells, “I’ve found something!” He waves to Toi and me to follow him. A dark mahogany cabin at the stern of the junk is wide with a low ceiling and we bend down to enter.

I wonder what poison I’ve taken to fall under this prejudice. Maybe I created this image for my own self-preservation, the concept that no one will mourn if I kill someone.

There, lying on a woven mat is a young girl with a frail, delicate face framed in coal silk hair. Thin white linen is draped from her chest to her ankles.

She seems sedated, not reacting to our presence, her eyes as if in a trance, just black pupils without tears staring at nothing. Brown stains are seeping out through the cloth. Toi gently lifts the cloth. Her burns shock me.

Her flesh is grotesque, tortured designs in shades of gray with thin white streaks of tissue drawn taunt like violin strings, stretching her young breast into unimaginable distortions, a startling contrast to her pale angelic face. Her chest, stomach and legs are oozing yellow pus. A foul putrid odor makes me gag and I fight the urge to vomit. I know it’s a sign of infection, maybe gangrene.

“Toi,” I say, “tell the captain we’re taking her to the hospital in Ben Tré. Taylor, get our stretcher.” Taylor starts to leave and then pauses. “Mr. Erwin, this isn’t our job. We’ll be out of our patrol area for the rest of the day.” Taylor’s formality is a sign. Whenever he disagrees with me, he addresses me as “Mr. Erwin.”

“Taylor, get the stretcher!” I shout. Taylor bolts from the cabin, kicking the door, his body language conveying fervent disagreement. I can hear it in his voice as Taylor yells at Moison to search the cargo hold, and barks at Hoffman to get the stretcher.

The captain of the junk squats next to the girl and I kneel on the other side. As Toi translates, the captain becomes agitated, speaking fast and loud.

“He’s refusing to let her go,” Toi says. “He thinks we believe this girl is Viet Cong—thinks we are going to put her in prison.” Toi pauses and then says, “Mr. Erwin, she might be Viet Cong, wounded in some battle.”

“For crying out loud, tell him this girl is going to die if she does not get to a hospital! Tell him she’s not going to prison. Ask him if this is his daughter.” I watch the old man’s eyes as Toi translates—I can tell when he hears my question. The old man looks at me and nods.

“Why is he refusing my help?” I ask Toi. “This is his daughter—a hospital can save her life.” Toi translates, but the captain just stares at me without responding.

I wonder if he cares. I’ve heard the Vietnamese don’t care about their children, that their culture is different. I now think it’s true. I believe the years of war have made the Vietnamese callous to human feelings, an entire country just trying to survive; the task too overwhelming to worry about the life of one child. They can always have more.

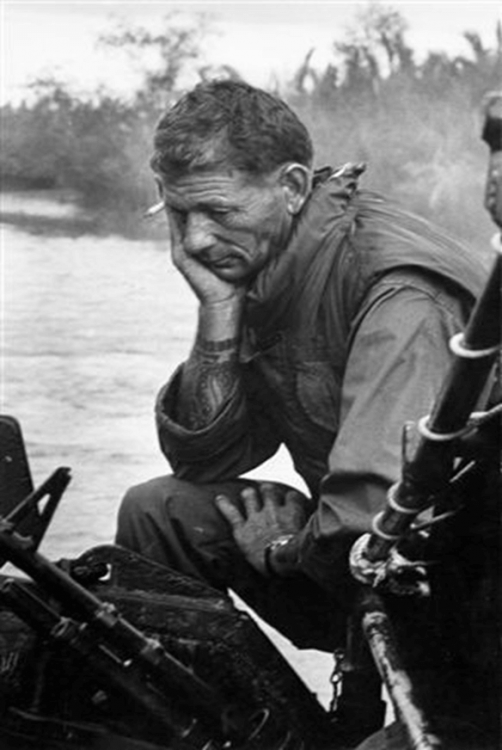

On a river in South Vietnam. I purchased this photo from the US Naval Institute Proceedings.

Hoffman crawls into the cabin, pulling the canvas stretcher behind him. The father is startled, rising up to his feet, yelling, screaming at me with a vehement protest, spittle flying from his mouth.

There’s no translation necessary. He’s four feet away, his feet and arms spread; muscles tense—his whole posture says he’s ready to fight, to sacrifice his life to prevent me from taking his daughter. I’m armed with a .38—the father with nothing but his body.

“He doesn’t trust you,” Toi says, “fears he’ll never see her again.”

Taylor comes back into the cabin with our medical kit. Toi translates as Taylor gives instructions for the burn cream, the sterile gauze and the morphine. The father begins to relax. Taylor turns to me and whispers, “Junk’s clean, no weapons, just fish and rice." Taylor pauses, and then says softly, “Skipper, please, let ‘em go.”

I want to help this girl—she’s close to death, but all I can say is, “Okay.” The junk pulls away from our side and I watch it motor upriver.

I wonder about Vietnamese values, about love for their children. Maybe I’ve been wrong; maybe they’re just like me.

I wonder what poison I’ve taken to fall under this prejudice. Maybe I created this image for my own self-preservation, the concept that no one will mourn if I kill someone. I’ll be off the hook, no bad memories for taking a life. I don’t think the young girl will live. In my mind, I still see the father cradling her in his arms as she closed her eyes. I don’t care if she is VC—she’s too young to die.

Story Themes: 1963, 1964, 1965, 1966, 1967, 1968, 1969, 1970, 1971, California, Cat Lo, Cat Lo Naval Base, Death and Loss, Humanity, Mekong Delta, Navy, Physical Wounds, Read, Reflection, Relationships, San Diego, Swift Boat, Swift Boat Sailors Association, Terrain, Viet Cong, Virgil Erwin