A Minnesota PBS Initiative

A Minnesota PBS Initiative

When I was at Washburn in ’65, a couple of soldiers came to our Civics Class to explain to the boys our obligation to register for the “draft” when we turned 18. They mentioned deferments, but insisted “Everyone will get drafted. No Exceptions!”

I didn’t know much, but I knew their math was wrong. We were the front-end of the baby-boom. There had never been enough desks or football uniforms for us. The Army wasn’t going to have room for all of us. And why would they need all of us to defeat some little guys wearing flip-flops? That was the day I began to suspect a hoax.

I registered at 18, and got my college deferment, eventually 5 years worth, so I didn’t have to confront the draft until Spring of 1970.

By then I knew stuff. I knew that we were going to lose the Vietnam War. So, by definition, fighting in it was for losers. Nobody I knew had been to Vietnam or was planning to go. I didn’t fully understand classism, but the poor fools going to Vietnam all seemed to be poor or black, never guys like me.

Some were inventing fishy medical conditions. Some were claiming to be gay, or getting married and having kids. None of these options seemed appealing.

Dodging the draft was a major topic in my social circle, and everyone I knew was finding a way. Some were joining the National Guard (military-light, in those days). Some were inventing fishy medical conditions. Some were going to Canada, or “underground.” Some were filing as Conscientious Objectors. Some were claiming to be gay, or getting married and having kids. None of these options seemed appealing.

My buddy, Dave (same draft board) got drafted. But the day after his scheduled induction, Dave was still around. Dave explained that he had “refused induction.” I didn’t understand.

Dave said that when the other young men, mostly farm-boys, stepped forward and raised their right hands, Dave didn’t. Then they yelled at him and sent him home. He didn’t know what would happen next.

Ninety days later, about the time I got my induction notice, Dave got a second notice. That’s when my Dave-plus-90-days-plan, came together. Dave had refused induction 90 days before me, so logically (in retrospect, it seems naïve to have believed that this was a logical system) whatever would happen to me, would have to happen to Dave 90 days earlier. Giving me time to think of something else.

So I reported to the Induction Station, spent half the day hanging out with about 20 minorities and farm-boys, roughly my age, all just as scared as I was, and when the Officer said to step forward - I didn’t. I know a lot of guys who served in ‘Nam think that draft dodgers were cowards. But I have to tell you that standing still, when the 20 guys I’d been hanging with all day all stepped forward; and the Officer screamed in my face that I was going to prison where I would surely be gang-raped, and still not stepping forward, was not an easy thing to do.

Dave kept getting draft notices, and kept showing up, not stepping forward, getting yelled at, and sent home. But it seemed like an awful nuisance to go through all that every couple months. So I threw away the second notice, and they stopped coming.

Until I was arrested and jailed. I made bail, and was scheduled for trial in August of ‘71, with 5 years for not stepping forward and another 5 for not reporting, hanging over my head. But I continued to be clueless, as though it couldn’t happen to me.

In court, the judge asked me if I had an attorney. I didn’t. He asked me if I wanted to waive my right to an attorney. I didn’t want to do that either. The judge was annoyed, “You have to either get an attorney, or waive your right to one. What is wrong with you?” When I said that I didn’t know any good attorneys, the judge laughed. I didn’t get the joke and was scared to death. The judge explained “There’s nothing in the constitution about a right to a good attorney. When you come for trial next Monday, bring someone licensed to practice law in Minnesota. I don’t care if he’s the worst lawyer in town.”

The lawyer was surprisingly upbeat about my situation, predicting that he could get the case thrown out in minutes. My trial lasted two days. The prosecutor had photos and multiple witnesses.

I sat down to ponder my predicament. As it happened, the next arraignment was another draft case. The attorney seemed 100 years old and apparently stone-deaf, but the outcome was a 90-day “continuance.” Again, the 90 days seemed attractive. So I followed this old man out into the lobby and tried to talk to him. He didn’t want to talk to me. When I blocked his path and begged him to take my case, he said, “I don’t do draft cases.” He gestured, disgusted, at his young client and said, “My grandson.” But I was persistent, and this old man, Francis Helgeson, a title insurance attorney, reluctantly agreed to see me on Saturday morning, 48 hours before my trial began.

Saturday, Helgeson was surprisingly upbeat about my situation, predicting that he could get the case thrown out in minutes. My trial lasted two days. The prosecutor had photos and multiple witnesses proving that I had not stepped forward. Helgeson kept asking me, “What’d he say?” A few times, Helgeson objected to something, but it would turn out that Helgeson had misheard what the judge or the prosecutor had said, and his objections were always overruled. And when it was our turn, Helgeson had nothing, “The defense rests.” The judge gave both sides two weeks to submit “written summations.”

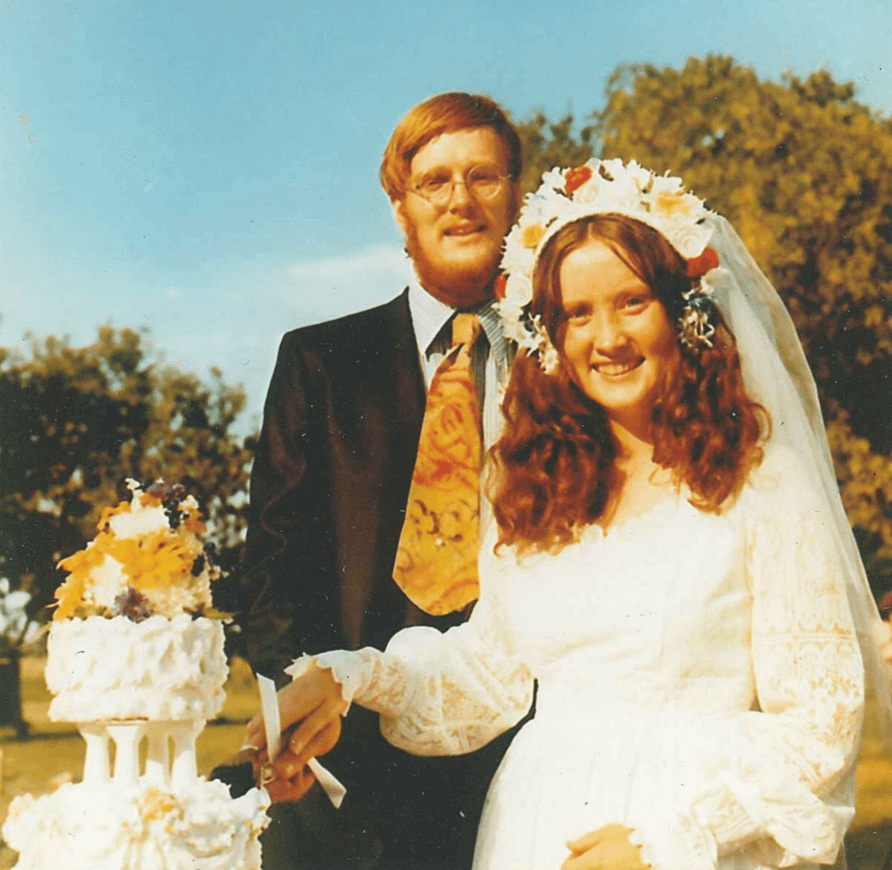

I was scared, but Helgeson was jubilant. I told him I was scheduled to be married on Saturday. Helgeson said, “Congratulations.” I explained we had planned a honeymoon to the West Coast. Helgeson said, “Have a nice time.” But I’m still on bail. I’m not allowed to cross state lines. “Don’t worry,” Helgeson said, “I’ll talk to ‘Phil’.” WHO?! “The judge, Helgeson explained, “We’re playing golf together on Saturday.” And suddenly, my future seemed brighter.

Helgeson was swamped with title insurance and had to keep requesting extensions, but finally submitted the summation.

The prosecution brief was 4 pages, all factual, proving the obvious - that I had not stepped forward. Helgeson’s “brief” ran 70 pages, calling attention to thirty-some procedural errors made by my draft board, any one of which would invalidate both my draft notices.

Though I had no legal training, I knew enough about American Justice to know that 70 pages of mumbo-jumbo beats 4 pages of facts every time. They could have redrafted me, but by ‘71, the guys running the war had figured out that guys like me were more trouble than we were worth.

Today, I have good friends who served in ‘Nam, mostly behind the lines. Some of them are proud to have served; some regret it. The main difference between them and me was that they didn’t know Dave, didn’t know that saying “No” was an option, didn’t have “middle-class privilege.” I am proud of my “service to my country,” in not stepping forward. My regret is that I hadn’t been more active in resistance, Because 47 years later, our country is still sending the poor and minorities to fight pointless wars.

Story Themes: Classism, Conscientious Objection, Court, Dissent, Draft, Draft Dodger, Induction, Jail Time, Race, Reflection