A Minnesota PBS Initiative

A Minnesota PBS Initiative

The following essay originally appeared on Rewire.org

and was reprinted with the author's permission.

Where do Hmong people come from?

Are they from Mongolia?

Why are you not Lao if your parents came from Laos?

These were some of the questions I struggled to answer as a 10-year-old. The other eager 10-year-olds waited for my answers. It was their first time meeting someone Hmong, an ethnic group with roots in Laos, Thailand, Vietnam, Myanmar and southern China. My native tongue tickled my classmates’ ears as they asked me to say things in my language, “Kuv lub npe hu ua… ” (“My name is… “) or “Kuv hlub koj” (“I love you”).

They would ask me write their names in Hmong, but I had no idea how to write in Hmong. In my mind, the written language looked like hieroglyphics. But I wanted to impress my new friends–I gave it my best shot and scribbled something that looked cool. They were impressed, and I slowly became a popular fifth-grader, not only with my classmates but also my teachers.

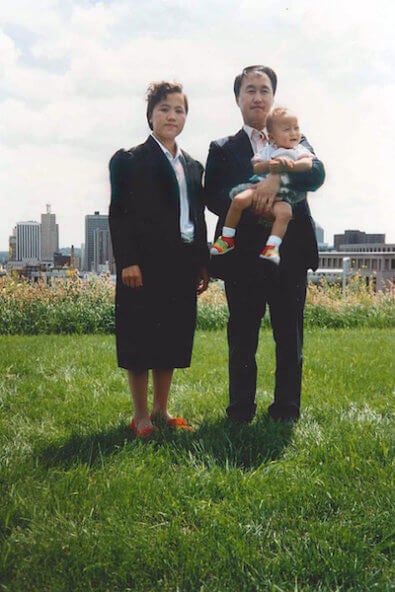

Kaolee Vang’s parents Yer (right) and Nengchue (left) pose with baby Kaolee a few months after arriving in America.

Code-switching to fit in

I grew up in a predominantly white community, the daughter of Hmong refugees who had high aspirations for their children. We moved to the suburbs of Blaine to evade the developing gang violence in the Twin Cities during the early 2000s. They feared my brothers and I would be initiated if we stayed.

Living in the suburbs, I struggled with my identity. At home, my parents expected me to speak Hmong and carry out my duties as a proper Hmong daughter. They spoke often of the struggles they endured during the Secret War in Laos, the U.S. government’s secret recruitment of Hmong soldiers to help fight the Vietnam War, in order to give their children a better life.

As a child I could never understand the depth of their experiences. The descriptions of hunger, restlessness, fear and danger seemed like a fictional novel.

When I started middle school I made my first Hmong friends since moving away from the Twin Cities. They were nice but I didn’t know how to act around them. I spent the previous years diligently code-switching–completely changing myself so I was easily accepted by my white friends. I had decided that Hmong was a useless language, so I didn’t speak it. Everyone speaks English, why shouldn’t I? I thought. I was split between two worlds.

This way of thinking created a huge divide between my parents and me. They felt they were losing their daughter. She was getting brainwashed by mainstream society. To me, my parents didn’t know any better. I was moving in the right direction but they constantly tried to pull me back.

I’m not sure why it had to be black and white. I now understand that the problem was me and my struggle with the gray area between being Hmong and American.

As I got older I was able to identify with my Hmong friends more. I could readily admit that I hadn’t seen the newest episode of “South Park” or that I did not pack my lunch because it would mean bringing a cup of rice and noodles. I didn’t have to explain myself every single time I turned down a birthday invitation because my parents didn’t trust “white people.”

I developed a false sense of “Hmong Pride.” I left my non-Hmong friends behind because they weren’t good enough anymore. I’m not sure why it had to be black and white. I now understand that the problem was me and my struggle with the gray area between being Hmong and American.

Connecting with my history

In college I found more stability and balance to my identity as a Hmong American. I met more Hmong students like myself with similar struggles. I took Hmong classes and enrolled in a Hmong minor degree program.

In my very first Intro to Hmong History class, we covered history that dated back to ancient China. The Hmong were known as the “Rice Paddy People” because we were the first to domesticate rice.

I learned we once had a Hmong king named Chi You. He was a fierce warrior who won countless battles against the Chinese dynasty kings.

When Chi You ultimately lost the war, the Hmong were eventually chased out of China and relocated to what is now Burma, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam.

Kaolee Vang’s family at the annual Minnesota Hmong New Year.

The Hmong lived in peace in the high mountains of Laos until the late 1800s when the French colonized the Kingdom of Laos and began taxing Hmong trading. Their relationship was tepid, at best, until World War II when the Hmong of Laos fought with the French army against the Japanese, earning respect and recognition for the Hmong people.

As a result, several Hmong were offered high-ranking government positions and people like Touby Lyfoung became heroes, their stories told from one generation to the next.

My people’s history unfolded before my eyes as we went from textbook to textbook. It had sounded so foreign from my grandparents, but here I was hooked on my history, hungry to know more.

So I continued doing research. And then we moved on to the Secret War.

My mother, an orphan after her father was assassinated and her mother remarried, lived with relative after relative.

Lost stories brought to life

The tragedies and sacrifices my parents and grandparents endured during the Secret War in Laos felt raw and real because it was raw and real. Class assignments encouraged us to talk with our elders to learn more, and it was then that I realized the depth of knowledge our community had access to. My parents, grandparents, neighbors and family had lived it. They knew.

Emotion and guilt hit me hard. My father was born into war, just as Hmong people were recruited into Special Guerrilla Units by the Royal Lao Army at the request of the United States CIA. From the moment of his birth, his father, uncles, cousins and grandfathers were absorbed by the war. At 10 years old my father held his first gun. By the time he was 13 years old my father had lost his father, brothers and several other family members.

Although there was an official “cease-fire,” the war never really ended for many Hmong people. My mother was a prime example of this. After the leading commander, General Vang Pao, was forced to escape the country, many families had to make a decision. Did they continue to fight for their lives? Did they surrender? Or did they try to flee and take refuge in another country?

My mother’s father decided to continue the fight. Other men felt similarly. They developed a rebellion and resistance group. Her family suffered the repercussions, casualties of their noble actions. My mother remembers going for weeks where they could only communicate in whispers under the blanket of darkness. They lived in the jungles where food was scarce; they witnessed family members, young and old, wasting away. Some died. In the end, my mother’s father was betrayed by his own soldiers and assassinated.

My father eventually escaped Laos and entered Thailand as a refugee, applying for refugee status in the United States of America. My mother on the other hand, an orphan after her father was assassinated and her mother remarried, lived with relative after relative. She eventually made it to Thailand and it was here that she met my father.

My father had returned to Thailand with his friends to see if they could offer any help to the families left behind. My parents fell in love and moved to the largest refugee camp in Thailand called Ban Vinai. It was there that in 1991 I was born. After my birth my father decided to return to America to work so my mother and I would have money for food, supplies and resources.

Once he was back in the U.S., my father wrote letters to his legislative representatives asking for guidance and support in sponsoring my mother and I to come to America. Our wishes were answered and in 1992 we left the camp to meet my father. I later found out that the Ban Vinai camp closed that year and many Hmong who were unable to gain refugee status to other countries were repatriated back to Laos.

My family now consists of my husband, father, mother, grandmother and two brothers and three sisters. As I think about how far my family and I have come, from the jungles of Laos to the busy streets of St. Paul, Minnesota, I have learned to embrace my identity as a Hmong American women, to live in that gray area.

Kaolee Vang is a Hmong American woman who is currently pursuing a master’s degree in marriage and family therapy at Saint Mary’s University. Kaolee’s long-term goal is to bridge generation gaps between parents and children through interaction and media. This year, Kaolee had the opportunity of providing her perspective and cultural background as the associate producer of the Twin Cities PBS documentary, Minnesota Remembers Vietnam: America’s Secret War.

Story Themes: America's Secret War, Ban Vinai, Ban Vinai Refugee Camp, Children of Veterans, Culture, Hmong, Kaolee Vang, New Beginnings, Refugee, Refugee Camp, Royal Lao Army, Secret War, Special Guerilla Unit, TPT, Twin Cities PBS